Wow, I’ve manage not to kill off the 2,000+ worms yet. They seem to be doing really well too.

For the last feeding (April 22) I dumped in the yard waste I had been collecting. It was bits violas and cosmos that were growing in the gravel, along with some grass. I also soaked some shredded paper and added that to the bag.

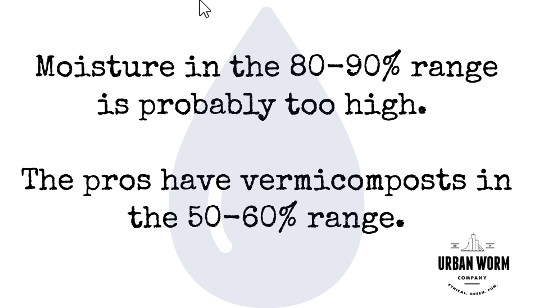

I thought it seemed dry, but I wasn’t clear on just what the moisture level should be. The worms seemed fine with it, but there were spots that the bag was only at 50-55% At one point it was down to 45% in a few spots. I started to spray the sides of the bad down 2x per day to bring it back up to the high 60 to low 80s. By that last feeding it was up to ~72% over all. I’ve been doing more searching on just what the correct levels of moisture should be. I’ve come down to a range of 60-70% as ideal. I’ve also ascertained from all the research that as long as the bin stays between 50-90%, the worms will likely be just fine. Gives you lots of wiggle room, eh?

From my favorite site on the topic:

I had also start to spray down the blanket when I was trying to get the moisture content back up. That seemed to be a big hit with the worms. They started crawling all over and in the blanket, and at times were on top of it. I don’t see any evidence that they are or were trying to escape though. Seemed that they were enjoying the condensation on the sides of the bag.

I’m still struggling with the urge to go digging around in the bin to see how things are looking below the surface. I also really want to find cocoons or small baby worms. This would indicate that the worms are happy and thriving, that is the goal after all. I’m also dying to try to shifting out the castings. I really want to see how much I can get and how it helps out the flower bed.

One of the other things I really want to figure out is just what type of worms that I have. See there are only really 7 types of composting worms out of the over 9,000 species out there. Composting worms are Epigeic means that these worms live and eat closest to the surface in loosely-packed environments like manure piles and the debris on the forest floor. They do not burrow in soil like the earthworms that we are used to.

I thought that I was ordering Red Wigglers from the two companies that I’ve ordered from…. I have since learned that they are more likely a mix of species. It’s another reason I keep taking so many pictures, I’m trying to see what species most of them are. So far I can’t really tell. I think most of them are the Red Wigglers, aka Eisenia Fetida, tiger worms, brandling worms, manure worms, panfish worms, and trout worms.

Note: red wigglers (Eisenia fetida) are an invasive species in North America, in regions where native earthworms are no long present. They were introduced from Europe. While red wigglers are beneficial in composting and gardens, introducing them into natural ecosystems can have negative consequences. Here’s why red wigglers are considered invasive:

-

- Non-native species: Red wigglers are not native to North America.

- Competition with native species: They can outcompete native earthworms for resources like food (leaf litter) and space.

- Soil alteration: Their rapid decomposition of leaf litter can alter soil structure and nutrient cycles, potentially impacting native plants and animals.

- Impact on forest ecosystems: In areas with no native earthworms, they can eliminate the leaf litter layer, which can be detrimental to young seedlings and other forest organisms.

- Non-native species: Red wigglers are not native to North America.

I would say that is enough geeking out, but I’m not done yet!!!

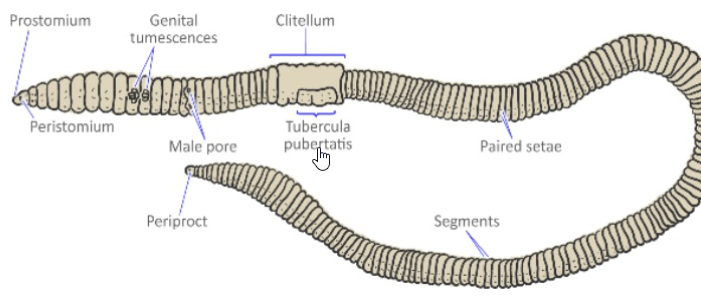

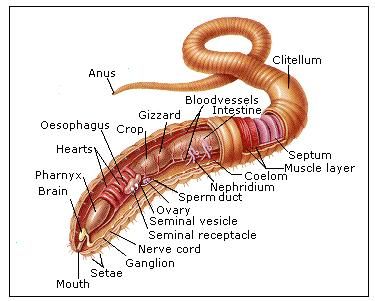

Next, up Anatomy! Below are a couple of diagram of the important parts of worms first up External, the second is Internal

From the Urban Worm Co.

The anatomy of a red wiggler resembles that of other common earthworms; a long-segmented body begins at the pointed head and terminates at a slightly-flatted tail.

A fleshy band called a clitellum features prominently on the body of the red wiggler at roughly 1/3rd of the length of the worm.

The digestive tract is simple, starting at the mouth where the worm begins to consume its food before passing it on to the pharynx.

The pharynx is a muscular section which acts like a pump to pull food into the mouth before pumping it out into the esophagus.

The esophagus is narrow and thin-walled and acts as the “waiting room” for the gizzard. The gizzard is the area where the food gets crushed and ground down before moving on.

Note: This need for grinding is why grit is recommended in a worm bin. The worm features no native grinding capability so the worm relies on ingested grit to help grind its food in the gizzard.

The stomach is where the first chemical breakdown of food happens with the help of a protein-busting enzyme. Calciferous glands in the stomach also serve to neutralize acidic foods passing through the worm’s digestive tract.

The intestine forms the longest part of the worm and is where the majority of digestion takes place via enymatic processes.

The castings eventually pass through the anus at the end of the worm as capsules coated with a biologically-rich mucus. (You’re not eating I hope.)

Did you know that worms are hermaphrodites’? Yes, they are!!! However it still takes two for breeding,

Okay, enough sex ed for today….

Back to Species.

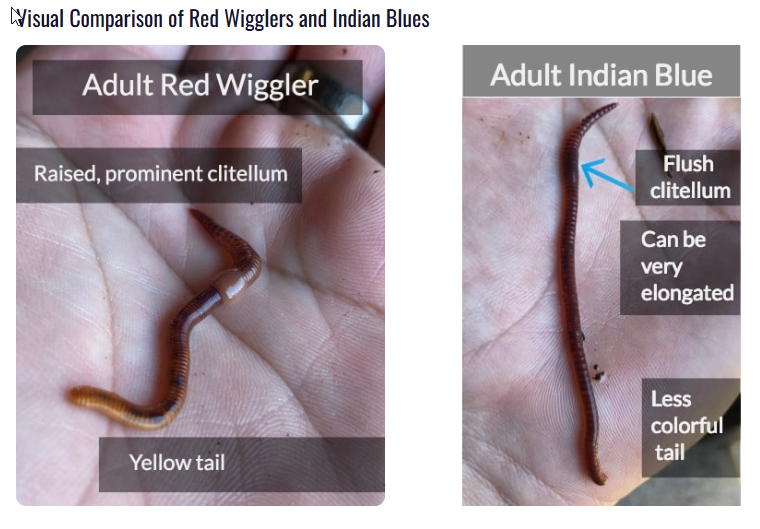

The other type that is very commonly found in the “red worm mix” is an Indian Blue, aka Malaysian blue, which is a tropical worm and prefers warmer temperatures. This could be a great thing for me as I want to move the bin outside for the summer. They do have a really big downside though, a tendency to try and escape, usually when there is an approaching thunderstorm, as they are sensitive to barometric changes. That could be a big downside for me during our monsoon season. They look very similar to the reds.

Another great pic from Urban Worm Co:

Okay… now I think I’m totally geeked out.